· Tom Hippensteel · Physics · 5 min read

Using Cosmic Rays to Catch Nukes in Space

An MIT researcher proposed using cosmic rays and a shoebox-sized satellite to verify the Outer Space Treaty's nuclear weapons ban for the first time in 58 years.

The Outer Space Treaty has banned nuclear weapons in orbit since 1967. For 58 years, nobody could verify it.

An MIT researcher just proposed a way to do it with a shoebox-sized satellite and the universe’s natural radiation.

Here’s the problem: Russia launched Kosmos-2553 in 2022. The US assesses that Kosmos-2553 is a testbed for components of a nuclear anti-satellite system, though not yet carrying the nuclear payload itself. If true, detonating it would wipe out most satellites in low Earth orbit. Starfish Prime did exactly that in 1962. A single 1.4 megaton blast increased the Van Allen belt’s electron population by orders of magnitude and crippled roughly one-third of all active satellites at the time, including the first commercial comms satellite, Telstar 1.

The Outer Space Treaty explicitly forbids this. But there’s no way to check. You can’t exactly ask to inspect a foreign military satellite.

Areg Danagoulian thinks you don’t have to ask. You just have to listen.

The Physics

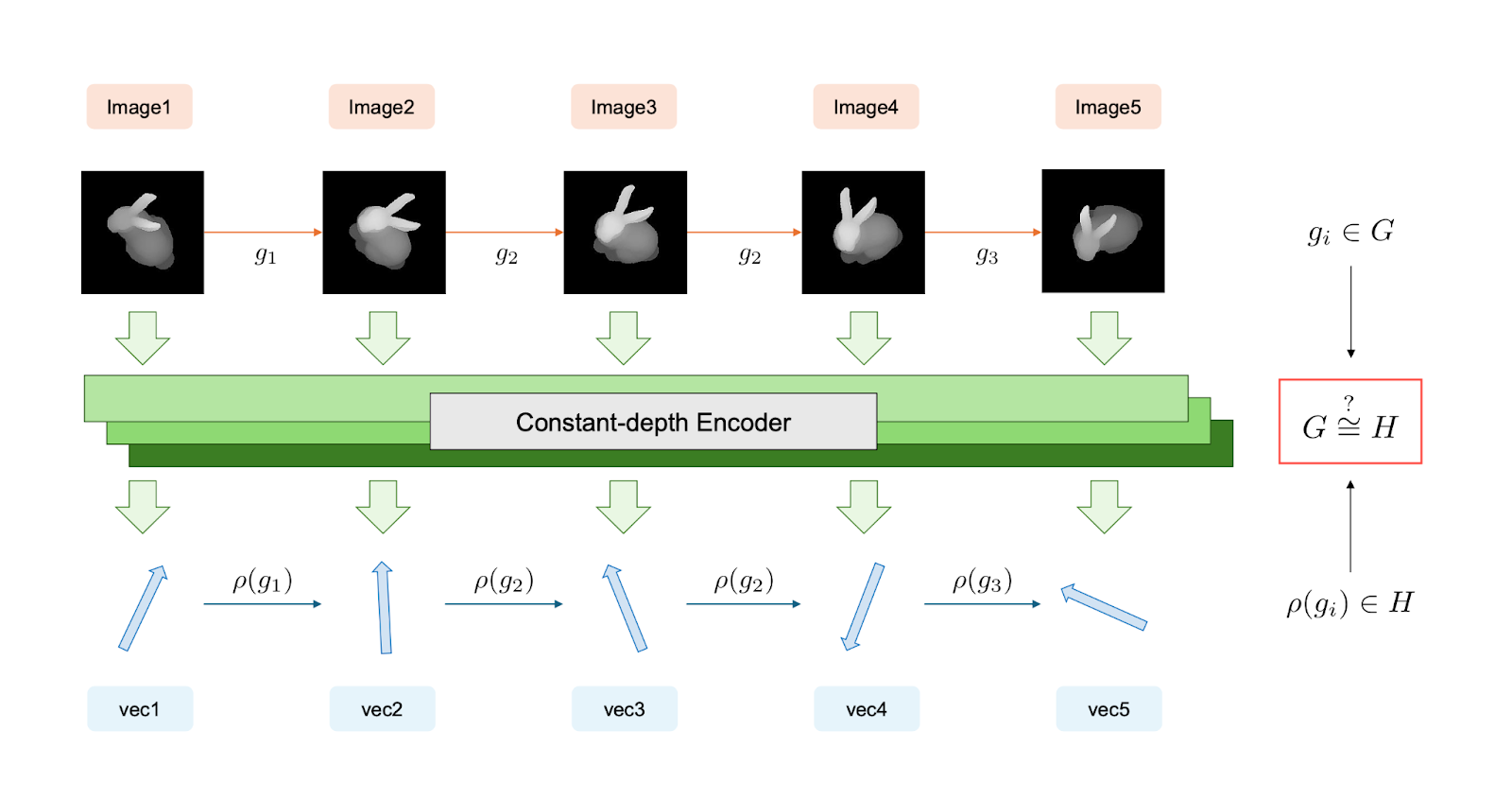

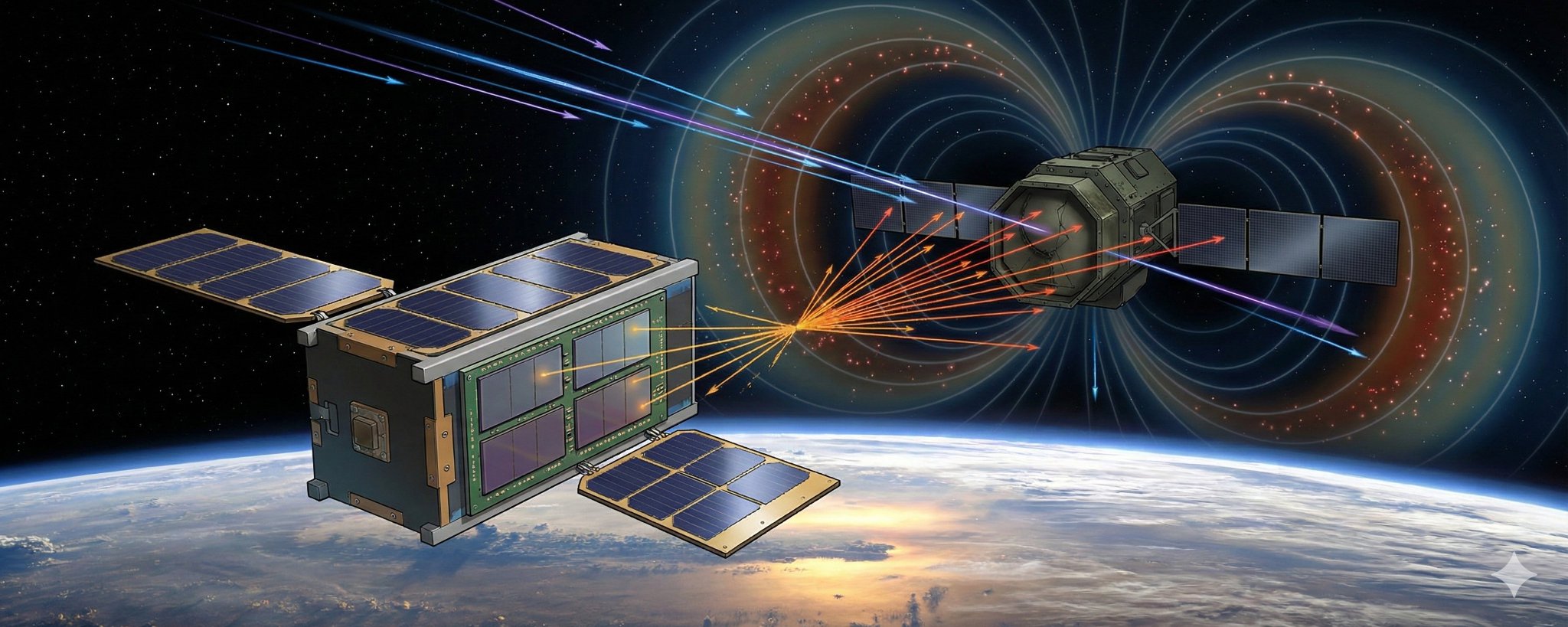

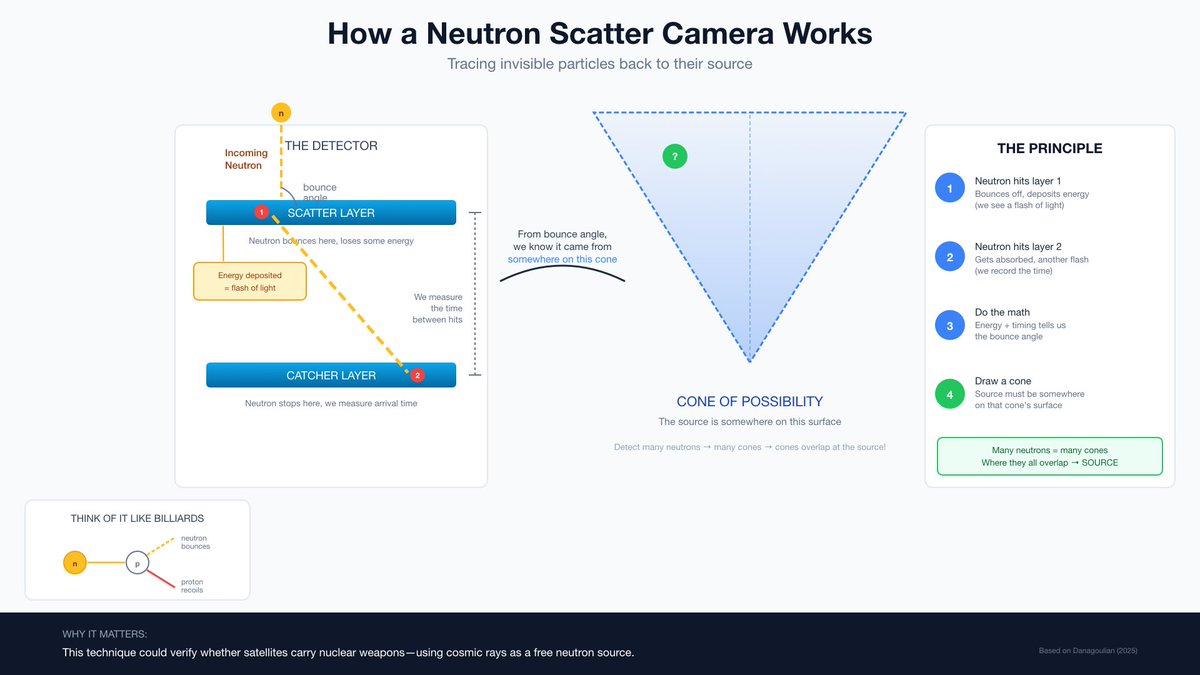

Figure 1: Catching the Invisible. To find a nuclear warhead, the detector tracks individual neutrons. By measuring the energy and timing of a neutron as it scatters through two layers of the detector (like a billiard ball), the system calculates a “cone of possibility” for where that particle came from. When thousands of these cones overlap, they reveal the location of the warhead.

The Van Allen radiation belts are full of trapped protons, some at GeV energies. These protons slam into anything in orbit. When they hit the uranium casing of a thermonuclear weapon, they produce neutrons through a process called spallation. Lots of neutrons.

Those neutrons have a direction. They come from the weapon. Background neutrons come from Earth’s atmosphere, from the inspector satellite itself, from everywhere else. Build a detector that can tell which direction neutrons arrive from, and you can distinguish “neutrons from that suspicious satellite above me” from “neutrons from literally everywhere else.”

That’s the core insight. Use the universe’s own particle accelerator to interrogate the suspect.

The Design

A 9U CubeSat. Two planes of 900 detector pixels each, separated by 10 centimeters. Each pixel: a neutron-sensitive scintillator sandwiched between diamond detectors that veto out the constant bombardment of protons and electrons.

The neutron scatter camera technique reconstructs incoming neutron trajectories. A neutron hits the first plane, scatters, hits the second plane. From the energy deposited and the time-of-flight, you calculate where it came from.

The math works out to 0.54% intrinsic efficiency, meaning about 1 in 200 neutrons from directly above actually registers as a confirmed detection. Sounds terrible until you remember the source is producing 10^10 neutrons every few hours. The detector collects enough signal to distinguish the warhead from the background noise.

The Numbers

From 4 kilometers away: one week of observation to confirm a thermonuclear device with 99% confidence.

Deploy ten CubeSats instead of one: 15 hours.

Close to 1 kilometer: a single flyby. One hour.

The paper includes a list of recent satellite close approaches (US, Russian, Chinese) all in the 4-12 kilometer range. None triggered a crisis. The inspection distance is politically feasible.

The Gaps

This is a feasibility study, not a flight-ready design. Danagoulian is explicit about what remains unproven.

The harsh radiation environment at 2000 km altitude delivers about 700 rad per week. Everything needs to be radiation-hardened.

Vacuum outgassing, thermal cycling, and actual sensor integration remain unaddressed.

The spallation model assumes an unshielded uranium casing. Real weapons might have shielding that changes the neutron signature. Or masks it entirely.

And perhaps most importantly: no one has tested whether this detector configuration actually works in orbit. The Monte Carlo simulations are solid, but hardware has a way of surprising you.

The Stakes

The Outer Space Treaty is nearly sixty years old. It’s been ratified by 117 countries including the US, Russia, and China. And for its entire existence, “trust but verify” has been just “trust.”

Danagoulian frames the threat directly:

“Such a device, if detonated, would destroy most of the satellites in the Low Earth Orbit.”

That’s not hyperbole. That’s Starfish Prime with modern satellite density. GPS. Communications. Weather monitoring. Intelligence. All of it, gone.

This proposal doesn’t solve the political problem of actually deploying inspectors. But it removes the excuse that verification is technically impossible.

Where This Goes

The physics works. The engineering looks plausible. What happens next depends on who picks it up.

If DARPA or a national lab takes interest: Expect a hardware prototype within 2-3 years. The component technologies (EJ-276 scintillators, CVD diamond detectors, CubeSat platforms) all exist. Integration and space qualification are the bottlenecks, not fundamental research.

If this stays academic: It becomes a citation in future arms control literature. Useful for policy discussions, but no closer to orbit.

The wildcard: Commercial space surveillance. Companies like LeoLabs and ExoAnalytic already track satellites. A private entity offering “nuclear verification as a service” sounds absurd until you remember that private companies now launch more rockets than governments. The incentive structure exists if insurance markets start pricing orbital nuclear risk.

Open Questions

- Can shielding defeat this detection method? The paper assumes bare uranium. What’s the signature through 10 cm of polyethylene?

- Does the detector work in reverse? Could you use this to verify that a satellite is not carrying a weapon, creating a certification regime?

- What’s the false positive rate? The paper claims zero background contamination with the directional cut, but that’s simulation. Real space environments are messier.

The Outer Space Treaty turned 58 this year. For the first time, someone’s proposed a way to actually enforce it. Whether anyone builds it is a political question. Whether it could work is now a physics question with a plausible answer.

Sources:

- Paper: arXiv:2512.20016v1 (December 23, 2025)

- PDF: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.20016.pdf

- Author: Areg Danagoulian, MIT Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering

- Code/Data: github.com/ustajan/kosmos

- Funding: NNSA, Carnegie Foundation, Longview Philanthropy