· Tom Hippensteel · AI Research · 4 min read

Deep Learning Might Have Been Lying to Us About Resolution

A new paper argues that flat error curves across resolutions aren't generalization. They're a frequency ceiling nobody was looking for.

TL;DR:

- The Observation: Physics models often show flat error rates even when tested at higher resolutions.

- The Suspicion: A new paper argues this isn’t “generalization,” but rather a “frequency ceiling” (Scale Anchoring) from low-res training.

- The Experiment: By aligning frequency embeddings across resolutions, the authors saw errors finally drop as resolution increased — behaving more like true numerical solvers.

Train a model on low-resolution data. Run inference at high resolution. The error stays basically the same.

For years, I’ve seen researchers point to this as evidence of successful generalization. The narrative is that the model learned the underlying physics, not just the grid, so it works at any resolution.

But after reading a new paper from MIT and South China University of Technology, I’m starting to question that assumption.

They call this phenomenon Scale Anchoring. And if their math holds up, a lot of “generalization” results might need a second look.

The Problem Nobody Named

From what I can gather, the issue comes down to frequency limits.

When you train on low-resolution data, there’s a hard ceiling on what frequencies that data can represent. It’s the Nyquist frequency (half the sampling rate). Mathematically, anything above that limit simply doesn’t exist in your training set.

So when the model runs inference at a higher resolution later, it encounters high-frequency components it has never seen. It’s essentially flying blind.

The result? The error “anchors” to the performance ceiling of the low-res training data. Go higher in resolution, and the errors stay flat. The model isn’t necessarily generalizing; it’s just not failing any worse.

Every Architecture Hits the Same Wall

The researchers tested this across most major deep learning architectures used in spatiotemporal forecasting — GNNs, Transformers, CNNs, Diffusion models, Neural Operators, and Neural ODEs.

They measured RMSERatio — the error at high resolution divided by the error at low resolution.

- For a numerical solver: This ratio should be <1.0. More resolution means less error. That’s the whole point of increasing resolution.

- For the DL models: The ratio stayed between 1.0 and 1.4.

| Architecture | Method | RMSERatio (64x Super-Res) |

|---|---|---|

| GNN | Neural SPH | 1.022 |

| Transformer | DeepLag | 1.021 |

| CNN | PARCv2 | 1.060 |

| Diffusion | DYffusion | 1.041 |

| Neural Operator | SFNO | 1.017 |

| Neural ODE | FNODE | 1.338 |

To me, that looks less like generalization and more like a hard ceiling.

Aligning the Frequencies

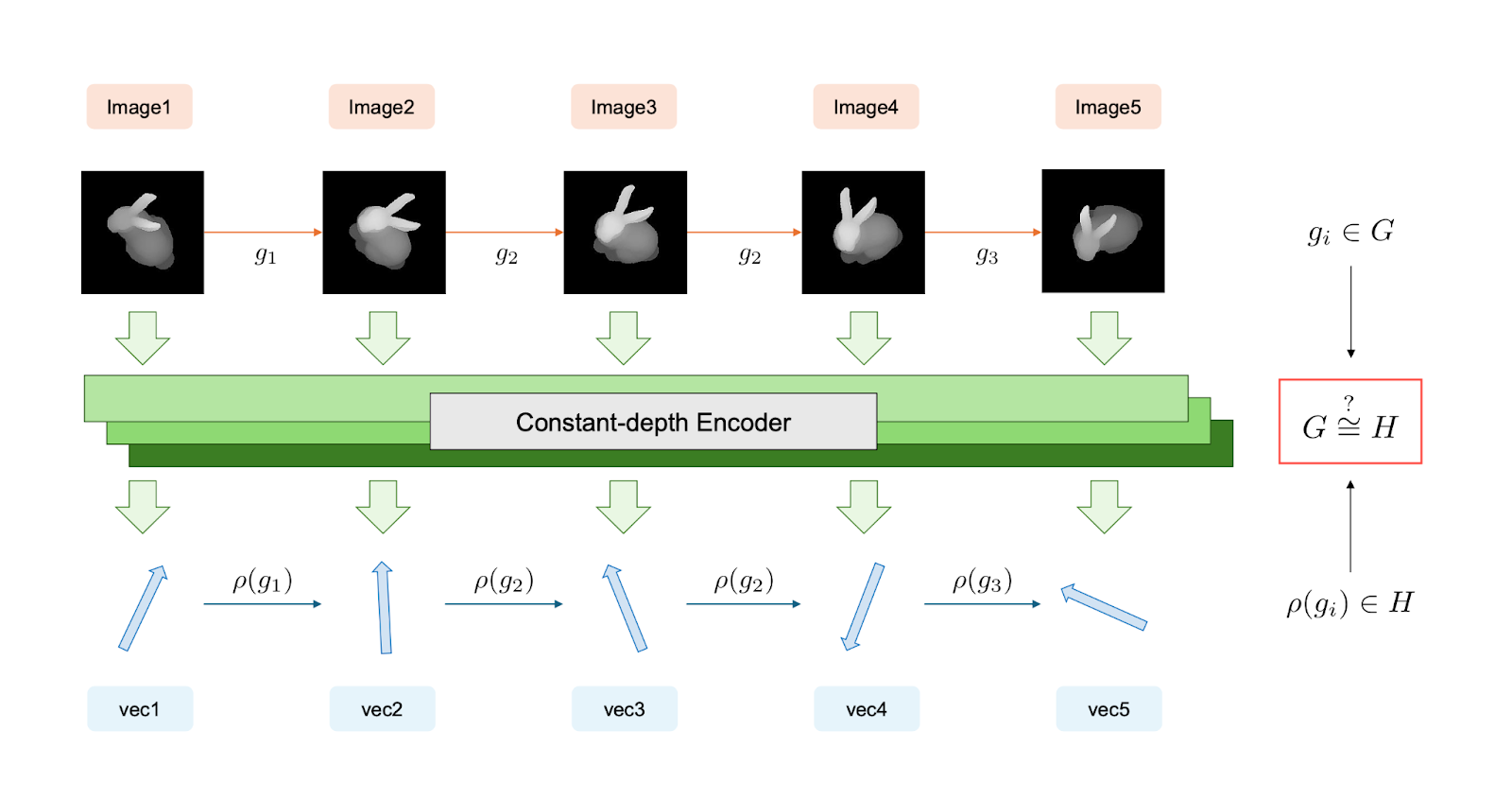

Their solution is called Frequency Representation Learning (FRL).

It took me a minute to wrap my head around the mechanism, but the core idea seems to be about creating a shared language for frequencies. They normalize frequency encodings to each resolution’s Nyquist limit.

Basically, they force the model to ensure that the same physical frequency gets the same numerical representation, regardless of the grid size. This theoretically allows the model to extrapolate spectrally, rather than just memorizing scale-specific spatial patterns.

The Results

This is the part that really caught my attention. When they applied this fix, the behavior changed drastically.

| Architecture | Baseline RMSERatio | With FRL | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNN | 1.018 | 0.175 | 5.7x |

| Transformer | 1.021 | 0.188 | 5.4x |

| CNN | 1.060 | 0.137 | 7.7x |

| Diffusion | 1.041 | 0.221 | 4.7x |

| Neural Operator | 1.017 | 0.135 | 7.6x |

The RMSERatio dropped well below 1.0 across the board. Errors finally decreased as resolution increased. It’s the first time I’ve seen some of these architectures behave so much like traditional numerical solvers.

The computational overhead seems manageable, too — training time increased 10-40%, but inference overhead was negligible.

What It Doesn’t Solve

I appreciate that the authors are upfront about limitations.

It turns out FRL breaks down at extremely high Reynolds numbers (Re=10^5) where turbulence becomes strongly nonlinear. The smooth frequency relationships the method relies on seem to stop working at those chaotic scales, and Scale Anchoring creeps back in.

They suggest future work could incorporate Kolmogorov-type spectral constraints, but for now, it seems best suited for moderate Reynolds numbers and weather forecasting tasks.

My Takeaway

If Scale Anchoring is as widespread as this paper suggests, it changes how I look at “generalization” graphs.

A model maintaining similar error across resolutions might not be learning the physics as well as we thought. It might just be hitting a frequency ceiling we weren’t looking for.

The fix proposed here is architecture-agnostic and seems to work well for standard use cases. But at the very least, it’s a reminder that a flat error curve isn’t always a success story.

Sources:

- Breaking Scale Anchoring — arXiv:2512.05132

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.05132

- Supporting: arXiv:1806.08734 (Spectral Bias of Neural Networks)

- ICLR 2021 — Fourier Neural Operator (Li et al., 2021)

- arXiv:2409.13955 (Neural Operators at Zero-Shot Weather Downscaling)